Breaking Down the Modernizing FedRAMP Memo

Aquia President Chris Hughes in this article breaks down the recently published Modernizing FedRAMP Memo from the Office of Manangement and Budget (OMB) and discusses key implications for the future of FedRAMP and its impact on the Federal and commercial cloud markets

We recently saw the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) release a memo titled “Modernizing FedRAMP”.

For those unfamiliar, the Federal Risk Authorization Management Program (aka FedRAMP) is a program the Federal government uses to securely adopt cloud services and offerings, and it is oriented around NIST 800-53 and associated security control baselines (Low, Moderate and High).

Cloud Service Providers (CSP)’s undergo an assessment and authorization process, receiving either a Provisional Authority to Operate (P-ATO) from the FedRAMP Program Management Office (PMO) or an agency issued ATO.

FedRAMP itself is a complex program with various stakeholders such as CSP’s, Third Party Assessment Organizations (3PAO’s), Advisors/Consultants, the FedRAMP PMO and agencies using and authorizing the cloud service offerings.

FedRAMP originated from a 2011 memo from the Federal CIO titled “Security Authorizations of Information Systems in Cloud Computing Environments”. Much has changed since that 12 year old memo that established FedRAMP and this “Modernizing FedRAMP” serves as a conduit to help the FedRAMP program align with the evolution of the industry.

Additionally, in 2022 we saw Congress pass the FedRAMP Authorization Act, codifying FedRAMP in law along with specifying requirements for the program and its operations. I previously covered the act in an article titled “Dissecting the FedRAMP Authorization Act”, which can be found here.

I have been building and securing cloud environments in the U.S. Federal and DoD space for roughly 8 years. I also previously served as a Federal employee at GSA where I was a Technical Representative (TR) for GSA for the Joint Authorization Board (JAB). My firm Aquia currently assists Cloud Service Providers (CSP) navigate the FedRAMP process with our Zero-to-FedRAMP (Z2F) offering, where we help accelerate FedRAMP Authorizations, leaning into modern tooling, processes and innovation. We bring years of FedRAMP experience coupled with deep Cloud Security expertise. If you’re a CSP looking to achieve your FedRAMP authorization and want to navigate the process smoothly and effectively, be sure to reach out!

The Modernizing FedRAMP memo represents some significant shifts in the future direction and approach of FedRAMP.

So what key changes does this modernizing memo seek to achieve?

Let’s dive in and take a look.

Background & Context

The memo opens laying out the background and context of FedRAMP. As we mentioned, FedRAMP was established in 2011. The primary objective is assessing CSP’s and their associated cloud service offerings against a baseline of security controls, derived from NIST 800-53 and establish authorization packages letting authorization officials, either at the FedRAMP PMO or agency’s, make risk-based decisions on granting Provisional ATO’s or agency ATO’s in the latter case.

The memo points out that initially the FedRAMP program and government primarily focused on Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) (e.g. AWS, Azure, Google Cloud et. al) but as cloud adoption matured, and the correlating growth of the distributed workforce and cloud in general, SaaS saw tremendous growth, and demand from agencies. There’s an acknowledgement that this trend was even further accelerated by COVID19 which saw the industry make drastic pivots to remote work and the associated SaaS based applications that enable it.

This trend and acknowledgement aligns with messaging I’ve written and spoken about extensively, such as the need for a SaaS Governance and Security Program and my involvement leading the publication of “SaaS Governance Best Practices for Cloud Customers” with the Cloud Security Alliance (CSA). Full disclosure, my company Aquia helps lead the only dedicated SaaS Governance and Security program that I’m aware of in the Federal landscape, which involves Discovering, Managing and Securing SaaS consumption. You can find out more on that front here.

Another key point the memo emphasizes is that as the use of Cloud has evolved and matured for the Federal Government, they’ve learned many cybersecurity lessons, and their approach needs to evolve (hence the memo).

There’s also the message that using commercial cloud services offers cybersecurity benefits to agencies, freeing up resources that otherwise would have to operate and maintain in-house infrastructure. This point of course will not be welcomed by the burgeoning cadre of Government contractors who have convinced the Government to self-host infrastructure and applications rather than consuming products as SaaS for example. This often occurs because GovCon service based companies make revenue via hourly rates and staffing, which isn’t bolstered by consuming SaaS rather than self-hosted infrastructure and applications.

This is prevalent among the expansive “Software Factory” ecosystem for example, particularly in the DoD, where programs often self-hosted commercial off the shelf software (COTS), which could often be consumed via SaaS while in many cases being more secure, elastic and capable.

The background context is wrapped up by emphasizing that the FedRAMP program must undergo strategic changes to continue to allow the safe use of commercial cloud for years to come for the Government.

Vision

The next section of the memo casts a renewed vision for the FedRAMP program. It summarizes the purpose of FedRAMP as:

The purpose of the FedRAMP program is to increase Federal agencies’ adoption of and secure use of the commercial cloud, while focusing cloud service providers and agencies on the highest value work and eliminating redundant effort.

That goal and the reality of course have always been a bit contradictory, especially as time goes on.

As I have pointed out in my previous FedRAMP article, there are currently only 318 total FedRAMP authorized services in the FedRAMP marketplace, in a broader market of thousands and potentially tens of thousands of cloud service offerings.

The vision touches on topics such as reusable approaches to security assessment and authorizations, reducing the nation’s cyber risks and contributing to a more stable technology ecosystem.

Some, including myself, would argue the risk is likely increased due to the un-intended impacts that FedRAMP as a compliance regime has had in impeding the governments access to innovative commercial cloud services and constraining the marketplace to only the most well resourced/funded and persistence commercial vendors willing to invest the capital and time it takes to endure the FedRAMP process.

Much like there is risk to using a technology, there are also associated risks with failing to innovate, leveraging commercial capabilities and furthering the friction that contributes to our civil agencies and warfighters losing their technological edge and being saddled with legacy technologies.

There’s also the reality that due to the cumbersome and complex nature of the FedRAMP process (and DoD Security Requirements Guide (SRG) on the DoD front) that it isn’t uncommon for many to seek workarounds and ways to leverage the cloud services without going through FedRAMP, leaving a slew of shadow SaaS and cloud usage flying under the radar of the very program that was created to govern it.

This same dichotomy applies to the broader Defense Industrial Base (DIB) who are exponentially utilizing SaaS and cloud in their support of the Government and are, in theory, required to use FedRAMP authorized or “equivalent” cloud services via sources such as DFARS 7012.

Thankfully, there’s an open recognition in the memo that:

The FedRAMP marketplace must scale dramatically to enable Federal agencies to work with many thousands of different cloud-based services that can accelerate key agency operations while allowing agencies to directly manage a smaller IT footprint.

The memo goes on to lay out specific strategic goals and responsibilities, including:

- Lead an information security program grounded in technical expertise and risk management

- Rapidly increase the size of the FedRAMP marketplace by offering multiple authorization structures

- Streamlining processes through automation

- Leverage shared infrastructure between the Federal Government and private sector

I won’t specifically rehash each of these at length, for that you can read the memo but I will touch on some key themes.

They include ensuring the FedRAMP security program and staff have the technical depth to review and identify weaknesses in security architecture of cloud providers. There’s also the notion that there should be an evolution of the authorization structures beyond the memo and those in place (e.g. Agency ATO and JAB P-ATO) to facilitate expansion of the FedRAMP marketplace.

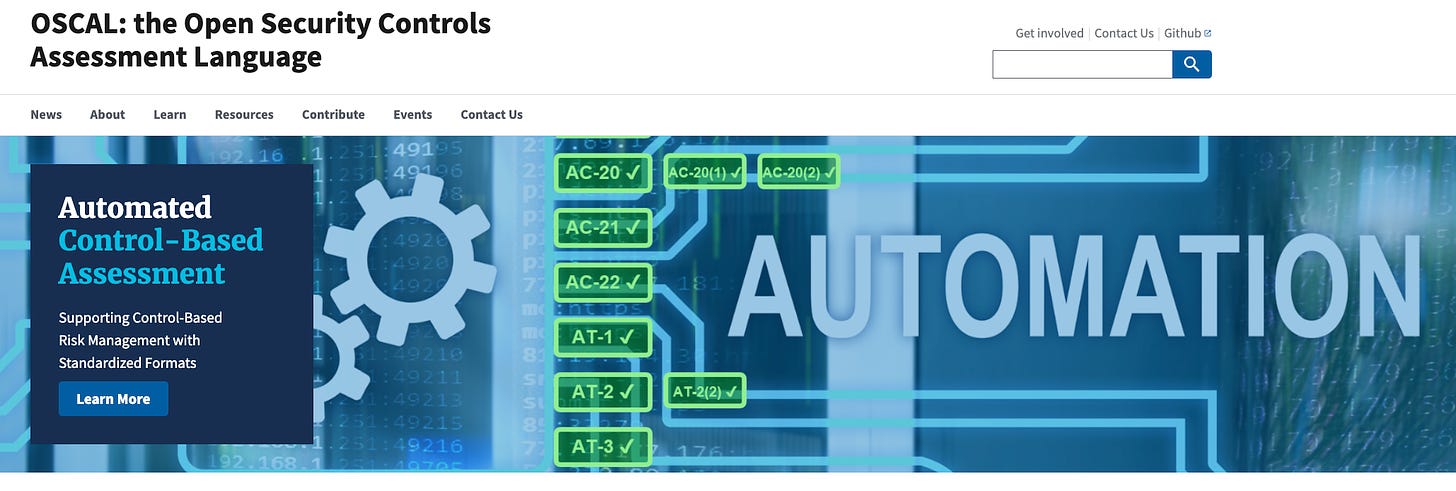

There’s the emphasis on the role of automation, specifically on the intake and processing of security documentation and FedRAMP authorization artifacts, by using machine-readable security documentation to facilitate speed and reduction of burden. The memo mentions “machine-readable” security documentation several times, and while it doesn’t specifically say “OSCAL”, also known as the Open Security Control Assessment Language, that is most certainly what the memo is referring to.

For those unfamiliar, OSCAL is an effort primarily led by NIST, to provide machine-readable representations of security control catalogs, control baselines, system security plans, assessment plans and their results.

The FedRAMP process (as well as DoD and Federal Risk Management Framework, and other compliance regimes such as SOC2, 800-171, CMMC etc. al) typically have a variety of artifacts such as Security Assessment Plans, Security Assessment Results, System Security Plans, Control Implementation Details and much more, all of which is historically communicated and exchanged in static documents such as PDF and Word. OSCAL promises to change that paradigm, ushering in machine-readable compliance artifacts, following other trends such as Infrastructure and Compliance -as-Code and soon, machine-readable attestations and vulnerability disclosures.

This shift to machine-readable artifacts enables key things such as a data-centric approach, integration with tooling and API’s and the ability to automate traditionally manual and cumbersome activities that have plagued compliance for decades, and helps bring Compliance into the era of DevOps and Cloud.

While OSCAL initially saw support from research communities and the public sector, such as NIST, it has now seen interest and support from tech giants such as AWS and Google. In June 2022, AWS announced they had achieved the first OSCAL formatted System Security Plan submission to the FedRAMP PMO, and in June 2023, Google Cloud announced their first complete OSCAL package as well, touting benefits such as transparency and automation.

Lastly the strategic goal is the use of shared infrastructure between the Federal government and private sector. Historically, CSP’s have established community clouds, dubbed “Gov Clouds” or “Gov Regions” (depending on the CSP), which were physically and logically segmented away from their broader commercial customer base to ease multi-tenancy concerns that communities such as Governments, Nation’s and National Security/Intelligence communities often have.

This goal represents a strategic shift, emphasizing that FedRAMP should not incentivize or require commercial CSP’s to create separate dedicated infrastructure for Federal use.

The importance of this shift cannot be overstated, as historically communities such as the Federal Civilian and DoD technology communities have experienced the pain of delayed features, capabilities and services as new and innovative cloud services make their way through the additional compliance workflows such as FedRAMP and DoD SRG to be accessible in Gov Clouds. Maximizing the use of commercial cloud infrastructure will limit some of the service and capability parity challenges that have hindered the Federal and DoD cloud innovation.

Leaning into shared infrastructure will, as the memo states, allow the Government to benefit from the investment, security maintenance, and rapid feature development that commercial CSP’s offer their general commercial customers.

One point I want to stress is that there is merit to segmentation, whether physical or virtual, and multi-tenancy security gaps, vulnerabilities and incidents can have a cascading impact, which is why sound security best practices need to be implemented, even in a multi-tenant cloud environment, especially when commingling Federal and DoD workloads with the broader commercial ecosystem.

We’ve seen no shortage of security incidents impact a CSP and have a ripple impact across their customers using their shared service offerings and infrastructure.

I cover multi-tenancy security concerns for cloud and best practices in an article titled “Troublesome Tenants”, where I use Wiz’s Cloud Isolation Framework as an example.

Scope of FedRAMP

After establishing the vision and strategic objectives, the memo goes on to discuss the current and to-be scope of FedRAMP.

It clarifies that the scope of FedRAMP as:

- Commercially offered cloud products and services (e.g. IaaS, PaaS and SaaS) that host information systems that are operated by an agency, or on behalf of an agency by a contractor or other organization

OR

- Cross-Government Shared Services that host any information system operated by an agency, or by a contractor of an agency or another organization on behalf of an agency

It also points out this only applies to unclassified information/data, not National Security Systems (NSS).

There’s also the nuance that FedRAMP doesn’t apply to cloud services that don’t host Federally operated information systems, either directly by the agency, a contractor or another organization on behalf of the Government. This commonly applies to ancillary services, publicly available services, social media etc.

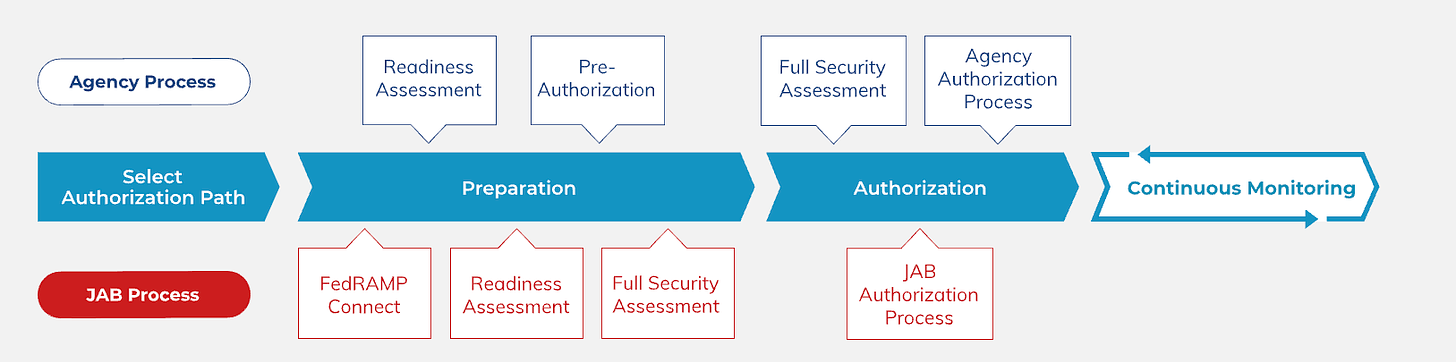

The FedRAMP Authorization Process

Now that high-level topics like scope and vision are out of the way, we get to the meat of the discussion, which is the FedRAMP authorization process itself.

This section opens by claiming that FedRAMP makes it “easier and more efficient for agencies to securely use cloud products and services”.

Obviously, I personally take offense to this claim, given that after a decade+, the FedRAMP marketplace has 300~ authorized services, in a market of tens of thousands. This claim simply doesn’t align with the reality of the outcomes, which have been anything but easy and efficient, as demonstrated by the market data.

Much like it is emphasized in the FedRAMP Modernization Act, the memo stresses the concept of a “Presumption of adequacy”, meaning if a CSP/service has a FedRAMP authorization, agencies are theoretically supposed to presume the assessment and authorization package are adequate and not force the CSP through the same burdensome process and rigor, minimizing the cost and burden on both the CSP and agency, although this doesn’t often play out in this fashion in reality, leading to significant rework, hence the memo and previous FedRAMP Authorization Act needing to stress the concept of presumption of adequacy.

All said, the memo goes on to clarify that agencies can determine they have a “demonstrable need” for security requirements beyond those in the FedRAMP authorization as well as being able to claim that the existing authorization package is “wholly or substantially deficient”. These claims will need to be vetted by the FedRAMP director for merit before allowing additional FedRAMP resources to it, and although not specifically called out, also avoid pushing additional toil and burden onto the CSP as well.

The concept of re-use of authorization packages isn’t new to the Government, and is commonly called “reciprocity” in NIST Risk Management Framework (RMF) parlance. That said, in a risk averse community like the Federal Government, re-use and reciprocity of authorizations is often more theory than reality and significant resources are often wasted re-validating authorization packages, both for FedRAMP and for DoD and Federal IT Systems under RMF ATO’s. Reciprocity is defined by NIST in publications such as 800-39 as:

Mutual agreement among participating organizations to accept each other’s security assessments in order to reuse information system resources and/or to accept each other’s assessed security posture in order to share information.

However, in practice that re-use and ability to avoid re-assessment has been elusive, especially in a risk averse culture that has perspectives such as trust but verify, and not invented here - leading to authorizations commonly going significant re-assessment and authorization toil. I will add, the skepticism around re-use isn’t entirely unfounded, as a practitioner who’s seen many ATO and RMF packages, the level of rigor and implementation varies widely, and I have seen some ATO’s that are in incredibly poor shape, with little control implementation, let alone details but are just “pencil whipped” into shape to have the compliance artifacts pass a high-level sniff test from an AO.

The memo goes on to explain how it will encourage authorization re-use by using multiple FedRAMP authorization types, including:

- Single-agency authorization

- Joint-agency authorization

- Program authorization

- Any other type of authorization

In summary, a cloud offering can be authorized by a single agency, multiple agencies, or by the FedRAMP Director/PMO themselves. Lastly, the “any other type of authorizations” speaks to the forthcoming innovations to the program that will be led by the FedRAMP Board (to be discussed below), which will promote the goals of the FedRAMP program, as we discussed above with the “Vision” section.

The memo stressed that regardless of the authorization type, assessment and validation of CSP claims can go beyond documentation and security controls and may involve red team assessments, penetration testing and other methods of examination and assessment.

Threat Information and Priorities

One specific aspect I wanted to highlight is that the memo calls for the use of threat information such as threat intelligence, analysis and threat modeling to help agencies prioritize control selection and implementation. This is an acknowledgment that despite the use of security control baselines, which include several hundreds of controls, not all controls are created equally and some controls should be prioritized for assessment and implementation above others, driven by identified threats and gaps. This is a push to move away from blanket uniform paper-based compliance and towards actual threat and risk management and true security.

Of course how much of this will occur in reality, and how much the security control baselines will be modified by the FedRAMP program remains to be seen, but the language is promising, if nothing more.

FedRAMP Ready

The memo specifically calls out the role of the “FedRAMP Ready’’ program/process. This shows cloud products and services that have completed a readiness assessment and is deemed acceptable by the FedRAMP PMO. This process/step is required for the FedRAMP JAB authorization route and optional but highly recommended for FedRAMP agency ATO’s.

It also often serves as a signal to the Federal market that a CSP is mature enough to endure the FedRAMP process and has done their due diligence to signal their preparedness, which is something that can help a CSP land an agency sponsor, which is required to go the agency route for a FedRAMP ATO. It can also help streamline the FedRAMP authorization process by completing some activities in advance.

The memo calls for the FedRAMP program to further explore FedRAMP Ready to serve as an on-ramp for additional SMB’s or disadvantaged businesses who provide innovative and promising capabilities but may struggle to enter the Federal market.

The memo also states that FedRAMP should provide additional procedures for the issuance of preliminary authorizations, this way Federal agencies can pilot the use of new cloud services that lack a FedRAMP authorization, but do so without needing to skirt the FedRAMP requirement - which is something that occurs regularly and there is currently massive use of non-FedRAMP cloud services across Government due to the significant burden and bottleneck that FedRAMP has served, only going agencies 300~ authorized cloud services to use in a market of tens of thousands. We essentially have massive shadow SaaS and cloud consumption of non-FedRAMP authorized services due to this reality. (hence my previous mentions of the need for SaaS Governance and Security teams)

Automation and Efficiency

As we have discussed throughout the article, one of the major challenges with the current FedRAMP program is the burden, time and manual toil involved, which is why it is refreshing to see the memo have a section dedicated to automation and efficiency. In fact the memo calls for:

FedRAMP processes should be automated wherever possible

Practitioners of course know that not all security controls can be automated, but many can, especially technical controls, and especially via API’s, Cloud and integrations, which I spoke about extensively in the FedRAMP Authorization Act article I linked to earlier on.

With the growth of cloud API’s CI/CD Pipelines and integrations, gone are the days (or should be) of entirely manual control compliance assessments which often rely on subjective determinations, sampling (due to the number of systems/configurations) and are error prone and time intensive. Cloud, CI/CD and declarative Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC) now allow us to assess systems in near real-time for their compliance posture, contrasted against applicable security frameworks and controls, and identify deltas in runtime environments and cloud configurations.

In fact, many of the leading IaaS providers such as AWS, Azure and Google now have native services to automatically assess the cloud environments against things such as CIS benchmarks, NIST and others, and this is incredibly useful given much of the FedRAMP market builds PaaS and SaaS applications on top of these underlying FedRAMP authorized IaaS environments. There are also several emerging GRC platforms and vendors, some venture backed, and others bootstrapped from industry specific experience, who also can help automate assessments and reporting.

For a more detailed look at how cloud changes the paradigm, I have articles such as “Compliance is Cumbersome, Cloud Can Help” and others where I discuss the evolution of the Shared Responsibility Model (SRM) to one of Shared Fate (pioneered by Google Cloud in particular).

Surprisingly, the memo states that GSA must establish a means of automating FedRAMP security assessments and reviews by December 23, 2023. This seems stunning, given that it is just two months away. This leads me to believe either they already have thought a lot about how to automate the assessments, or they will miss the deadline. Let’s hope it’s the former.

To help achieve this goal, the memo once again emphasizes the importance of FedRAMP rallying around “machine-readable artifacts” (e.g. OSCAL as we discussed and other emerging forms), via API’s that allow for self-service integration between the FedRAMP team and the CSP’s directly. This is such an important step forward for the FedRAMP team to pursue because it eliminates a lot of the subjective human involvement and foolish approaches like sampling and leans into machine-readable artifacts, objective data, automation and technological innovation.

Compliance hasn’t kept pace with DevOps, Agile and Cloud and this will help change that and bring compliance out of the stone ages of digital paper based artifacts and manual toil.

The memo states that the FedRAMP PMO will work with entities such as NIST, OMB, CISA and the private sector, such as providers of modern GRC tooling to enable the machine-readable artifacts, integrations and use of API’s to automate traditional assessment and authorization activities.

Security Control Inheritance

Moving beyond technology, the memo stresses the importance of procedural efficiencies as well and calls out sharing controls between cloud products and services to rely on underlying platform and infrastructure.

While not called out by name, they are referring to a concept known as “control inheritance” and is defined by NIST as:

A situation in which a system or application receives protection from controls (or portions of controls) that are developed, implemented, assessed, authorized, and monitored by entities other than those responsible for the system or application; entities either internal or external to the organization where the system or application resides.

Security control inheritance is incredibly common in cloud environments and is a practice used by entities such as DoD/Federal Software Factories who build on top of authorized IaaS and PaaS environments and is in practice within FedRAMP too, often leading to the creation of artifacts such as a Customer Responsibility Matrix (CRM) which lays out what controls a system inherits from a control provider (e.g. underlying IaaS/PaaS or organizational level controls), what controls are a shared responsibility and what are left to the system owner (or CSP in the case of FedRAMP). Think of a SaaS provider building on top of a FedRAMP authorized AWS IaaS environment and the controls they could either fully or partially inherit, accelerating their authorization timeline and minimizing their burden and cost of compliance in the process.

These inheritable controls should be well documented by the FedRAMP PMO already and the associated IaaS/PaaS CSP’s and not need to be re-assessed or worried about.

Existing Industry Frameworks

Another significant point of focus of the memo is the acknowledgement that many CSP’s have already pursued and obtained other industry certifications for existing frameworks. It doesn’t specifically name them, but there are many examples, such as SOC2, HITRUST, ISO 27001 and others.

I actually penned an article on NextGov/FCW all the way back in June 2021, when the Executive Order came out, showing how the Cyber EO, in Section 3 called for GSA, OMB and FedRAMP to collaborate to:

Identify relevant compliance frameworks, mapping those frameworks onto requirements in the FedRAMP authorization process, and allowing those frameworks to be used as a substitute for the relevant portion of the authorization process, as appropriate

Now, here we are almost 3 years later and the “Modernizing FedRAMP” memo is pushing for this to become a reality, albeit later than we all had hoped.

The memo calls for maximizing the use of existing frameworks, certifications and assessments to avoid unnecessarily slowing the adoption of cloud services by the Federal Government.

This of course includes the need to map existing frameworks to FedRAMP control baselines, understand where existing frameworks and certifications can be leveraged either partially or in whole. The memo even calls for leveraging external security control assessments and evaluations in lieu of newly performed assessments and letting some certifications serve as “full FedRAMP authorizations, especially for lower-risk products and services”.

While there are still a lot of details to be flushed out on this one, it shows a continued willingness, at least in writing/word (not action yet), of the Federal Government and FedRAMP to accept, at least to some extent, other compliance frameworks and certifications in place of FedRAMP or use them to minimize the burden of FedRAMP to some extent.

Continuous Monitoring

Achieving a FedRAMP authorization is but a milestone. Even after achieving a FedRAMP ATO, CSP’s still need to participate in what FedRAMP defines as continuous monitoring and is documented in documents such as their “FedRAMP Continuous Monitoring Strategy Guide”.

Continuous Monitoring, or ConMon as it is called for short, involves activities such as monitoring and remediating weaknesses since the last assessment, monitoring changes to control implementations and dealing with newly discovered vulnerabilities.

While in theory it seeks to keep FedRAMP from being a snapshot-in-time, it suffers the same fate as most compliance schemes oriented around legacy processes and tooling, which is that it is largely manual, primarily only gives insight at the time of assessment, and becomes a cumbersome activity in its own right.

Again, this is where innovative tooling, platforms, cloud services, API’s and automation can help improve ConMon to become a much more near real-time visibility and governance activity than a paper-based performative art.

The memo goes on to layout how the FedRAMP PMO will work with the FedRAMP Board, CISA and others such as OMB and DHS to develop an updated ConMon framework with some key themes, such as:

- Agility, automation and DevSecOps practices

- Minimizing advanced approval from Government for CSPs to make changes

- Providing insight and visibility to CISA

- Avoiding incentivizing bifurcating cloud services into commercial and Gov focused instances

- Clarify expectations around incident response procedures, communications and reporting timelines

These efforts look to modernize the FedRAMP approach to ConMon and make use of modern tools, technologies and methodologies while improving the visibility and governance of FedRAMP authorized cloud services while minimizing burden and toil.

Roles and Responsibilities

After ConMon, the memo goes on to discuss roles and responsibilities. I won’t belabor all of the roles and responsibilities because it’s safe to assume most of my readers aren’t in the designated roles, and if you are, you’re likely familiar with the responsibilities you will have based on the memo.

That said, I did want to touch on a few things here.

The FedRAMP Board

The memo discusses the role of the “FedRAMP Board”, which consists of up to even senior officials from agencies who are appointed by OMB in concurrence with GSA. It has to include one rep from GSA, DHS and DoD and others as OMB determines.

It states that the board memos must possess technical expertise in cloud, cyber, privacy, risk management and other relevant skills.

The board will provide key input such as recommendations for FedRAMP requirements and guidelines, best practices and more.

Technical Advisory Group

Much like the FedRAMP Board, the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) will provide relevant subject matter expertise to FedRAMP and key advisory insights on recommendations and improvements. It claims the TAG will serve as an “independent source” for technical and programmatic best practices.

All TAG members will be Federal employees.

You’ll notice that despite language around industry engagement, collaboration and more, both the FedRAMP Board and TAG are composed exclusively of Federal employees.

This simply isn’t ideal in my opinion, given:

- The Federal government doesn’t have carte blanche on cloud security expertise and could benefit from direct industry membership and participation in these groups

- While industry may be engaged, ultimately these two groups serve as the primary voices that likely get heard by the FedRAMP PMO and others

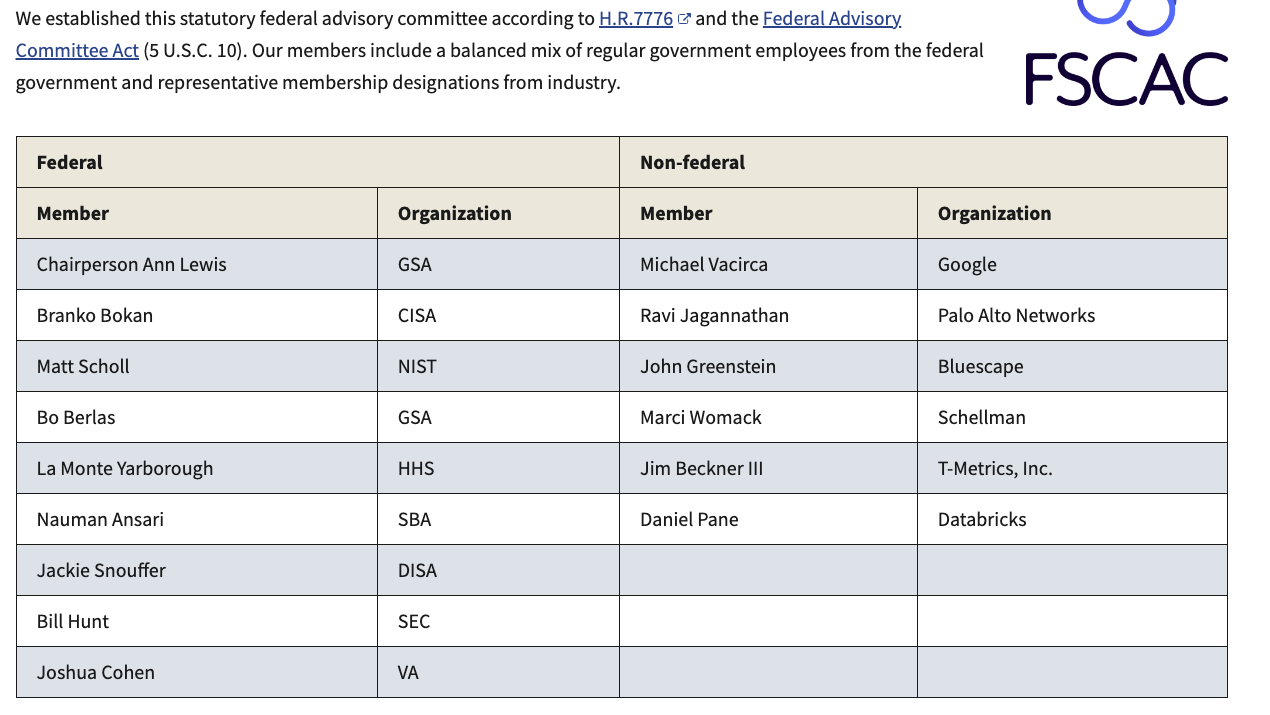

There is of course the recently established “Federal Secure Cloud Advisory Committee’’ but you’ll notice it is numbered 9 to 6 in terms of Federal to non-Government members, and even then, the non-Government members come from large organizations such as Google, Palo Alto and Schellman, giving small business no formal voice or seat at the table, despite FedRAMP having a disproportionate impact on SMB’s due to FedRAMP’s cost and burden, something that primarily large companies (such as those with seats in the FSCAC) can shoulder - hence the reality that there are only a few hundred cloud services in the FedRAMP marketplace, since it is an achievement out of reach of most resource strapped smaller organizations, regardless of how innovative and promising their cloud service offering(s) may be. \

In my opinion this leaves small CSP’s largely unheard in the FedRAMP dialogue and therefore, likely out of reach for Federal agencies to collaborate with.

Industry Engagement

The memo has a section dedicated to “Industry Engagement”, where it says FedRAMP serves as a bridge between the Federal community and commercial cloud market.

Many would, and could, based on FedRAMP marketplace figures we’ve mentioned several times, would argue that FedRAMP functions much more like a regulatory moat or raised drawbridge than an actual bridge with the commercial cloud marketplace. As we have seen, in a market of tens of thousands of commercial cloud services and providers, only a very minor subset of providers and services are actually FedRAMP authorized and legally available for Government consumption.

Nonetheless, the memo states via GSA and the FedRAAMP board, there will be industry engagement through the FSCAC to understand industry technologies and practices that FedRAMP can use to improve.

Implementation

Last but not least the memo lays out some key implementation deadlines I will summarize below:

- Within 90 days OMB will appoint the initial FedRAMP Board members and they must approve a charter for the group once selected

- Within 90 days and annually GSA will submit a plan to OMB detailing programmatics like staffing and budget and progress on implementing requirements from the memo

- Within 180 days each agency must issue or update their agency-wide policy to align with this memo and agencies most promote the use of cloud products that meet FedRAMP requirements (e.g. opting for commercial cloud products over paying GovCons to build competing government off the shelf products)

- Within 180 days GSA will update FedRAMP’s ConMon process to reflect the principles in the memo

- Within 1 year GSA will produce a plan approved by the FedRAMP Board and collaboration with industry to structure FedRAMP to encourage the transition of agencies away from the use of Government-specific cloud infrastructure (enabling the adoption of true commercial cloud innovation, not Government community clouds which often lag in service and capability parity)

- Within 18 months of the memo GSA will build on the memo to receive FedRAMP authorization and ConMon artifacts exclusively through automated, machine-readable means (this is a stretch goal but I would love to see it materialize and it could have very promising implications for the growth of the FedRAMP marketplace)

Conclusion

While imperfect, the Modernizing FedRAMP memo by OMB represents several significant strategic shifts in the FedRAMP program to help improve its current processes, tooling and rate of authorizations. It also signals further commitment to the FedRAMP program by the Federal Government, especially when coupled with the FedRAMP Modernization Act.

One thing that is clear is that FedRAMP is and will remain the primary pathway for cloud service providers looking to get their offerings into the Federal marketplace and access a market that spends tens of billions annually on IT and only plans to further invest and lean into cloud computing to power missions from Federal Civilian agencies to National Security and the Department of Defense (DoD).

If you are a CSP with any interest in the Federal market, you should be sure to familiarize yourself with the FedRAMP program and process.

My firm Aquia currently assists Cloud Service Providers (CSP) navigate the FedRAMP process with our Zero-to-FedRAMP (Z2F) offering, where we help accelerate FedRAMP Authorizations, leaning into modern tooling, processes and innovation. We bring years of FedRAMP experience coupled with deep Cloud Security expertise. If you’re a CSP looking to achieve your FedRAMP authorization and want to navigate the process smoothly and effectively, be sure to reach out!

If you have any questions, or would like to discuss this topic in more detail, feel free to contact us and we would be happy to schedule some time to chat about how Aquia can help you and your organization.